I recently completed a month-long challenge, shooting with the same camera and lens and posting a photo each day in an online photography community. My camera of choice was the Pentax K-3 Mark

III Monochrome, and my lens was the HD DA 15mm f/4 Limited. It’s a wide-angle prime lens which

equates to about 22.5mm on the APS-C sensor, very close to the classic 21mm focal length.

Why did Pentax choose to come close, but not exactly match the classic 21mm with this lens? It’s

an open question, but they have done it with all or nearly all of their Limited series of

lenses, both the DA for crop sensors and the FA for full frame. It’s part of the unique Pentax

charm, I suppose. They dare to be different, so why shouldn’t I?

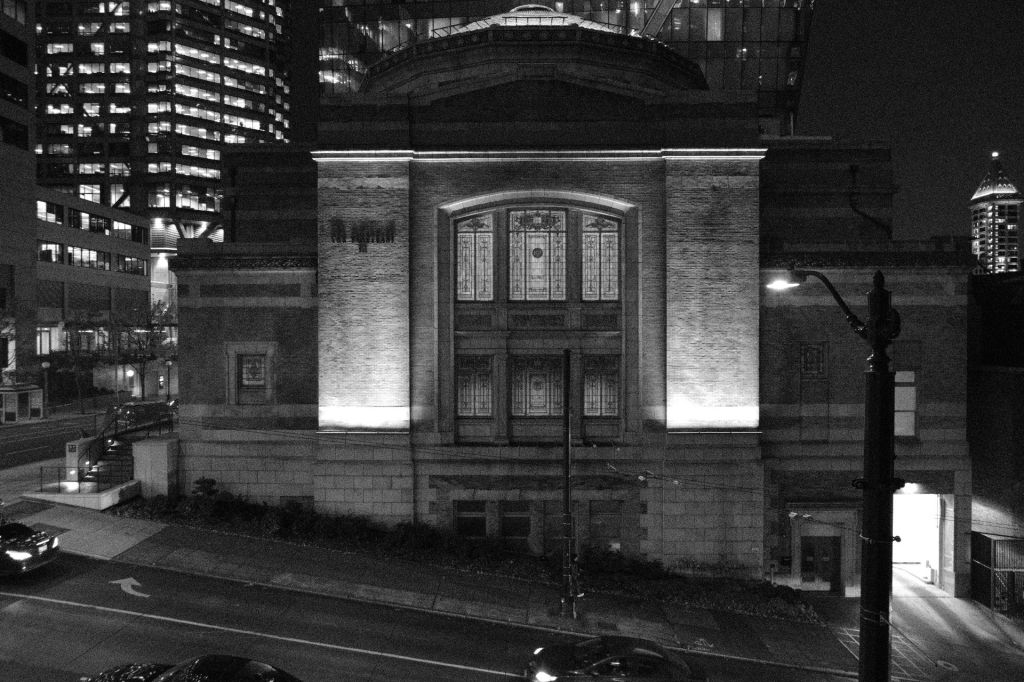

And different is certainly a good way to describe the camera and lens combination. Not only was

I restricted to an unusual, and very nearly ultra-wide, focal length, but in a dedicated

monochrome camera to boot. This presented some challenges for me, since I had to come up with an

image (which I could bear to present to other photographers) every day.

Fortunately, I have always taken to shooting with a wide-angle lens. The field of view can be

difficult to navigate if you are struggling with omitting distractions in your frame, but the

secret with these lenses is simple enough: get closer. Wide lenses will magnify your subject as

you narrow the gap between subject and lens – it’s part of the distortion, the ultra-wide

effect, you can get, but if you know how to manage it, you can use it to your advantage.

From my years with the 28mm-equivalent lens on the Ricoh GR series, I learned the wide-angle

characteristic which I call “push-pull.” I can’t remember whether I cribbed this language from

someone else (it’s likely enough, since we all become sponges during our learning period with

photography). I don’t claim the concept as my own, but it goes something like this: the greater

the distance to your subject, the more a wide-angle lens will “push” your subject away from the

photo. This means that they become less prominent relative to the background elements. The

closer in that you get, the more that the lens will “pull” your subject to wards the camera and

the viewer. They’ll grow larger relative to background elements. Of course, this works with any

foreground elements which are close to the camera as well, so you can use this for expressing

creative relationships between elements.

When you combine the “pull” factor with the surprisingly close minimum focus distance of most

wide-angle lenses, you will find that you can get quite close and isolate your main subjects

quite well. This may not work for human faces, since you will tend to find the nose and other

facial features will lose their normal proportions. This can offer some whimsy or humor to some

shots. When used carefully, you can really emphasize small things, like objects in a still life

image, or insects, or… the list is limited by your imagination.

I found my chosen combination to be very engaging to my creativity, and the combo made a

surprisingly good one for snapshot shooting, as well as a bit of street photography. I will

follow this up with another article on the more technical aspects of the gear, and how I found

it to perform. For now, thank you for reading!